Fuller Craft Museum.

“In 2018, guest curator Glenn Adamson selected ten artists to participate in the project with the charge that only 17th-century technology and processes be used in the creation of the objects. To fuel and inspire the work development, the artists and project partners participated in two research trips – the first to Plymouth England in March 2019, followed by Plymouth, Massachusetts in April 2019. These immersive experiences created a sense of communion amongst the artists while providing important scholarly, historical, and technical information to inform the development of the work. The resulting artworks illustrate exceptional technical skill, while also speaking to the social realities behind the material culture, and the examination of the Mayflower crossing through a contemporary lens. For some, the Mayflower voyage and subsequent settlement of Plimoth Colony is a treasured historical event, while for others, the colonization and treatment of the Wampanoag peoples illustrate imperialism and cultural ruin.”

About Another Crossing: Revisit the Mayflower Crossing

A touring exhibition recognizing the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower crossing and its significance to American and world history. Developed in partnership with Fuller Craft Museum, Plymouth College of Art, and The Box (both in Plymouth, England), Another Crossing brings together artists from the United States and Europe for a global, cross-cultural effort that examines a pivotal event in world history.

Through Another Crossing, the artists respond to this complex part of our history and its impact on our culture over the last four centuries.

ARTISTS: Annette Bellamy Sonya Clark David Clarke Michelle Erickson Jeffrey Gibson Jasleen Kaur Christien Meindertsma Jonathan James-Perry Katie Schwab Allison Smith.

Research and Process

During the initial research week held in Plymouth, UK, there was a profoundly moving presentation by Dr. Stephanie Pratt (Former Reader Art History Plymouth University). At the end of her talk, I approached her with the serious intent of finding a golden ticket out of this project. I introduced myself as a white, European middle-class man with serious concerns about my ability to have a legitimate comment on the Mayflower and its historical impact. I was hoping I had found my exit strategy. However, she scuppered me when she said, and I paraphrase – “It’s bigger than two nations, this is about humanity, and the clearest way we can discuss this is through art.”

There is no better time than right now to start to confront the Mayflower crossing history and acknowledge its consequences – as these are still playing out today. It’s become evident when we examine this story that there are two distinct camps: those that have gained and those that have lost.

The Mayflower represents a story full of social propaganda, speculation, hearsay and myth. So it’s been surprising to learn how little actual ‘evidence’ exists, with almost all representation depicted from a white European perspective. Nevertheless, the legend of the Mayflower and its human cargo perpetuates today.

Images that began to form the foundations of the project. Contradictions, hearsay, myths and speculation were everywhere.

I knew from the beginning that I did not want to work with a recognizable form; as this is a tried and tested route for me.

I had to wrestle with every aspect of; material choice, appropriate processes and relevant tools.

The layers, details and their associations run deep.

There is for me little fact and almost all representation is depicted from a white European perspective.

This still perpetuates today.

Who are the curators, the authority, the writers, the academics, the painters………..? Who’s voice is heard, who is muted?

What are these supposed facts based on and where is the evidence. What can be relied on as truth and where do we need to dig deeper and is it not time for some truths to be acknowledged?

The material was my entry into the project. Not a form or object but the metal itself. Through a conversation with artist Jonathan Perry, I was fortunate to find a metal that connected both the European immigrants and the indigenous peoples. Both cultures had the same view of this particular metal, the same relationship with it, and an agreed knowledge. Lead facilitated the fighting that ensued in the Pilgrim land-grab. It directly relates to death; if it didn’t kill outright, it poisoned the wounded.

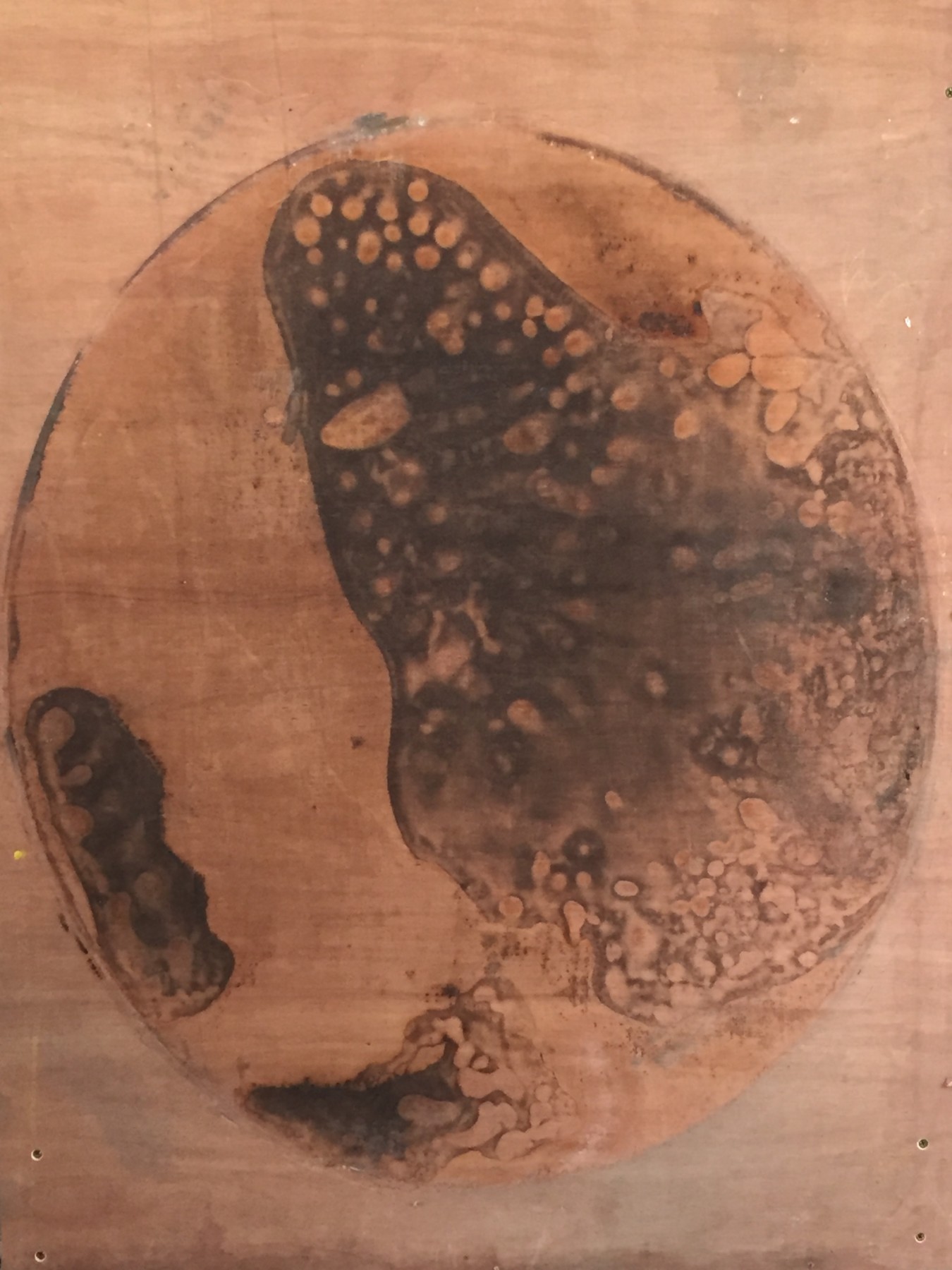

I melted lead shot for my casting. I chose not to remove any oxide slag or scum in the casting process, and everything went into the portrait “guts ‘n all.” A direct contradiction to the tradition in casting that only the ‘clean/purest’ metal is used.

My goal was to suffocate, dominate and overpower one material with another. I intended to force two opposing materials together in a collision, a direct and brutal encounter. Molten lead was poured over hand-woven linen, a fabric used for clothing and oil painting canvas.

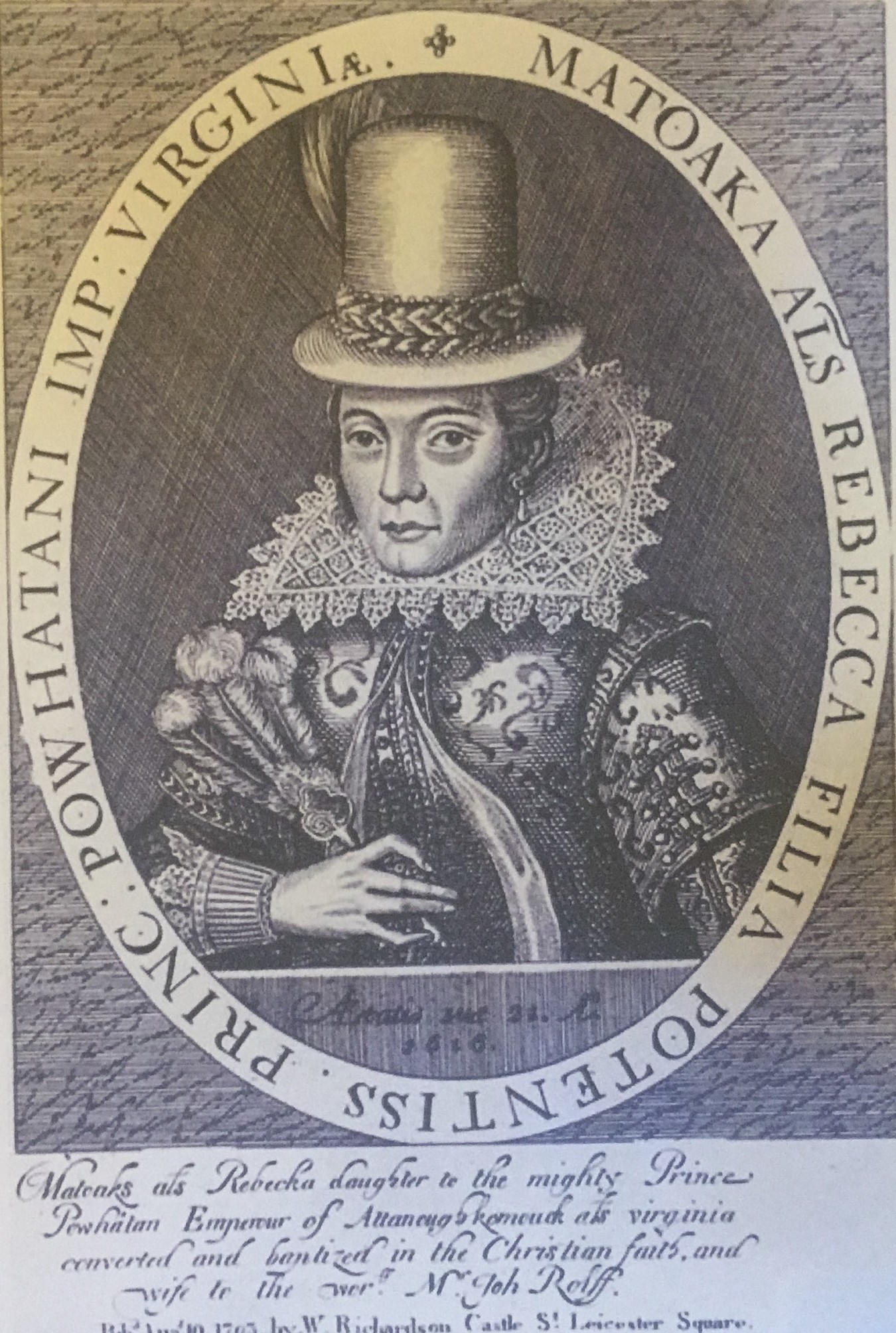

The classic oval format often seen in portraiture was my inspiration for the form of the piece. In addition, I wanted to reference a portrait of Pocahontas, a Native American, in the Smithsonian’s collection and use its precise measurements.

Pocahontas is romanticised, Disneyfied and even turned into a doll figure, forced into marriage to John Rolfe, a tobacco farmer so that her family’s land could be “acquired”. She was then shipped off to England, dressed up in European clothing and presented to English society as an example of the “civilised savage”. She never returned to her home, died March 1617, and is supposedly buried in Gravesend, UK.

The Smithsonian. USA (92.7 x 80 x 6.4cm. Artist unknown

Miniature Poor Traits informing: shape, scale and process

I melted down second-hand lead shot to use for casting. In the casting process, I chose not to remove the oxide slag or scum. Instead, everything went into the portrait. I intentionally wanted the piece to be heavy, to weigh as much as the average human body: 62 kilograms. The final artwork was, in fact, closer to two human beings.

After some research, I picked Oak gall, a natural dye to colour the cloth. It’s a parasitic growth that develops on oak trees as the female wasp lays a single egg in developing leaf buds. Once invaded by wasps, the tree becomes infested with the larvae that feast on tree whilst being protected by gall.

Since the time of the Roman Empire, oak gall has even been used in the production of ink. It’s alleged that a printing press was on the Mayflower to produce news or propaganda.

The last technical detail in using the natural dye is that it needs a mordent or ‘fix’ to stabilise it, which involved a donation of several litres of my stale piss.

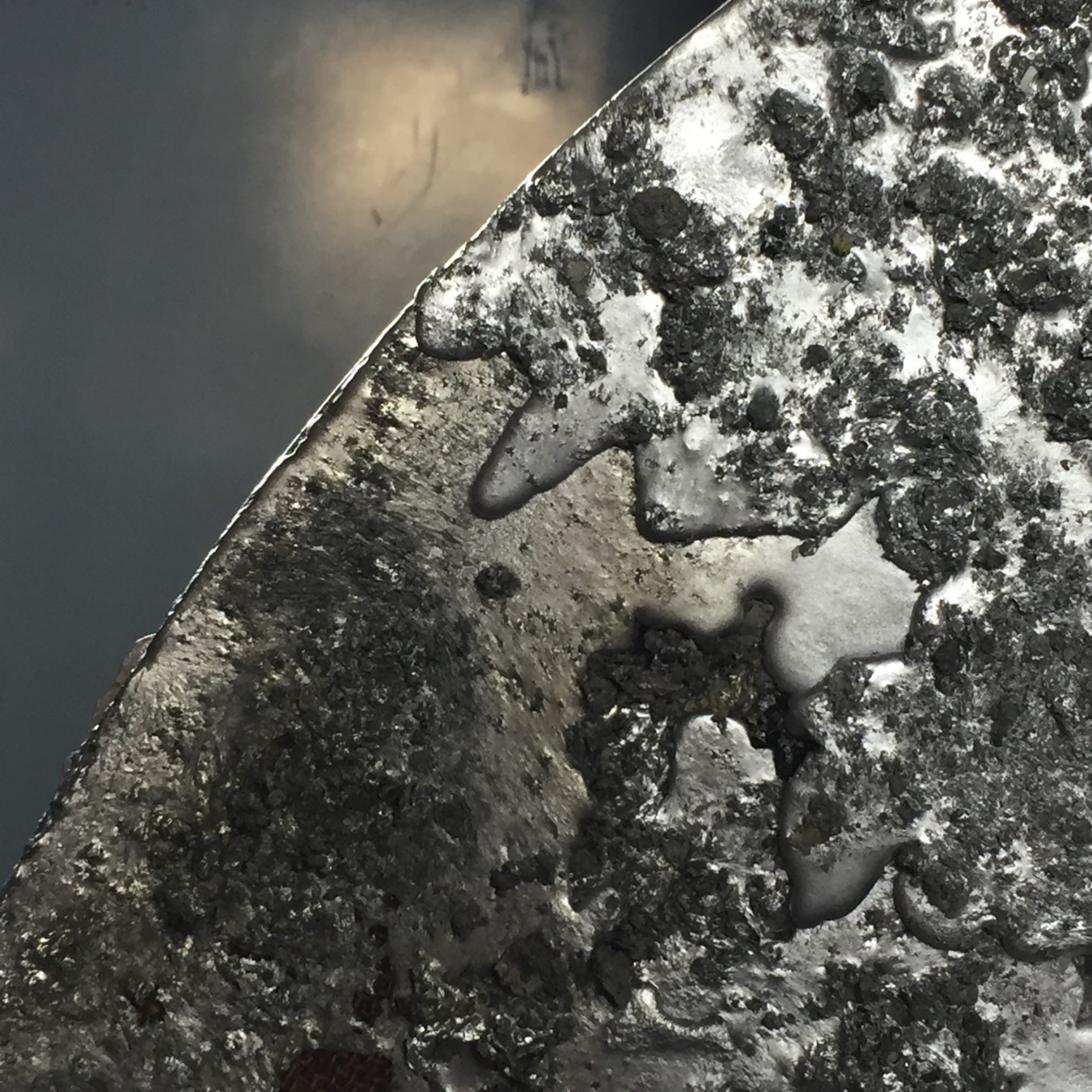

I commissioned two other makers to produce elements for me. Julian Coode, a blacksmith, was instructed to make the oval-edged former that I could cast within. In addition, he also forged the butcher’s hook and o’ring, which represented a full-stop, a punctuation mark. I chose not to create specification drawings; instead, I applied a trial-and-error method using direct measurements.

Textile artist Lucy Rhodes was given the task to weaved Irish linen, known as Tow linen. Again, I provided measurements that she applied to her old eight shaft countermarch weaving loom. The resulting fabric was rough, somewhere between cloth and canvas. It was not elegant or refined, and there was a rawness to it. Fortunately, the loom’s width just matched the dimensions of the portrait’s form, with only a few millimetres to spare.

POOR TRAIT

The title ‘Poor Trait’ revealed itself to me during the making process whilst at my bench. It’s a classic Clarke title, a play on words, and an indicator of how I feel about this historical event. I see no celebration here but a moment to reflect how poorly men behaved towards others. It’s a head-on collision where the consequences are still being playout today. The final artwork makes this tension clear, with a wave of hot toxic material that suffocates, dominates and infests. Purposefully, there is no cleaning up, no polishing, no ‘finishing’. I’ve left the work in its rawest state, just at the moment when one material invades another. It’s a particular piece in that the more you look, the more you see.

It was critical to ‘lynch’ the piece to hang off-centre on the iron butcher’s hook that punctures the canvas skin. I wanted it to look cruel and brutal, in the same way, a suspended animal’s carcass would. But, by placing it off-centre, it creates a sense of unease and awkwardness. Like a wonky picture on a wall, the viewer should itch to straighten it. But, instead, it should be an irritant, never resting easy.

Unlike most portrait paintings, Poor Trait has neither a front nor a hidden back – only sides. All sides of the story exposed with nothing hidden, the front-facing and back-facing all revealed. A fragile relationship between two materials comes to the fore, who dominates, who supports what will collapse under the weight? Roles, relationships and hierarchies all come into play.

There is only the final piece; every scrap of initial making ended up in the pot.

Poor Trait consumed everything.

For me this show has been all about the journey, all about the process. That’s true of its main subject, of course – a voyage – but also the experience of working with each artist. It’s been such a powerful experience to learn about their own individual practices, and see them rise to the challenge of the project.

It isn’t possible to right past wrongs, but art can provide a space of reflection, awareness, and restorative justice.

Glenn Adamson, Guest Curator